In response to the murder of abortionist Dr. George Tiller, the Houston Chronicle’s editors asked a pertinent question today – “When does anti-abortion rhetoric cross the line from free speech?”

Before I begin, a question in return: from free speech into what, exactly?

Presumedly the editors mean a criminal act. Fair enough – speech is either free or prohibited by force of law or the threat of same. The boundary of our protected First Amendment rights is circumscribed by the jagged, piecemeal line of preceding incitement rulings.

The law, imperfect as it is, draws the final line in the sand at the end of free speech. As such, the standard ought to be heavily weighted in favor of the speaker and the burden of proof placed on those who would restrict speech. Anything not explicitly forbidden is permitted.

Incitement to violence is one such legitimate prohibition of speech and radicals who call for violence are in violation of that standard. Such cases are particularly egregious when committed with premeditation; conversely, we would be wise to overlook extemporaneous utterances, even when repulsive or offensive. After all, no one can claim to control his or her tongue without fail.

Angry, even hateful speech should not be criminalized, while deliberate incitement must be, for a crime is in the action, not in the talking, and to incite is to act deliberately.

To this end, the editors rightly point out that “[Bill] O�Reilly had excoriated �Tiller the baby killer� and his �Nazi stuff� for several years, as had Operation Rescue and other abortion foes.”

Did O’Reilly act with the intent of inciting Tiller’s murder? It’s unlikely to say the least that such a case could be made, if only for the simple fact that O’Reilly’s quoted description of Tiller’s profession is, above all, accurate.

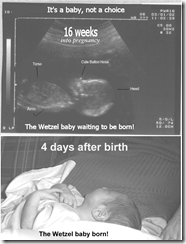

Tiller�s was one of only three centers in the United States to perform abortions after the 21st week of pregnancy.

If a hard line is to be drawn the law, fully restrained by the state’s burden of proof, must be the tool used to make the final mark separating legal speech from the illegal.

Yet the law should, in addition to being the final solution, also be the last. Is it necessary to have decades of mindless shouting over issues such as abortion? It’s obvious that neither side’s extremists can ever be satisfied and that a compromise no one likes will eventually be agreed on.

Abortions are not generally available after 16 weeks in most of the civilized world. It is inevitable that the debate in the United States eventually settle on a similar standard. The only question is how many more babies – and how many more abortionists – must die needlessly before that happens.